Storytelling as Liberation

Third-generation Chinese American speaker and activist Nikole Lim shares how her family history and cultural identity shape her work advocating for survivors of sexual violence.

By Dr. Michelle Reyes

M

ore than ten years ago, inspired by women she had met through her travels, Nikole Lim felt compelled to leave a successful career as an international photographer and filmmaker to start a nonprofit in East Africa called Freely in Hope. The organization equips survivors and advocates to lead in ending sexual violence through their rewritten stories.

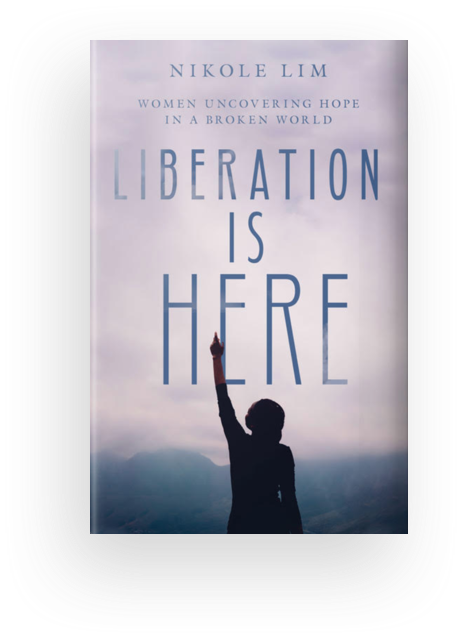

The speaker, educator, and storytelling consultant is also releasing her first book, Liberation is Here: Women Uncovering Hope in a Broken World (InterVarsity). In it, Nikole tells the story of how she started Freely in Hope, the women she ministered to and who ministered to her, and how she has been changed by the journey.

I spoke with Nikole recently about her work, the tensions it created within her Chinese American family, and God’s role as the ultimate transformer of our narratives. This interview has been edited for length.

Your book is dedicated to “my Gung Gung, who told me to write before I knew how.” How did your grandparents teach you to be a storyteller and how has your cultural heritage informed your approach to storytelling?

My grandfather was a journalist in Communist China. One night, he got a tip from a Communist soldier telling him that he was blacklisted and going to be killed in the morning. He fled from his village to Hong Kong, and eventually made it to Canada and from there to San Francisco, where he became the first Chinese-speaking pastor in Chinatown.

He always brought this notion of storytelling and visual storytelling through the photos he would take both in Chinatown and in rural China, where he returned after his retirement. The stories he would send back about what he was doing and what the people were doing were always full of laughter, joy, and hope, despite the hardship and oppression they lived in. He would always leverage the hopelessness and despair and the death he daily saw with the joy, love and hope his family had for him. It was how he told those stories that really resonated with me growing up.

Your grandfather sends you pictures of people from China, including the Bai peoples, and it’s these pictures that create a tension for you in terms of the lived experiences of Chinese peoples. In other words, not all Chinese are the same. Can you speak on why it’s important for us to deconstruct our single narratives of whole people groups?

The beauty of a lot of the images that my grandfather sent me was that every tribal people had a different way of dressing, eating, communing--every culture had different colors as representation of who they were and their royalty and their tribal alliances. I think that color variation is really indicative of the variation of all Asians. There are thousands of experiences and nuances as there are shades and hues of color. In the same way, every tribe has its unique nuance that we can learn from.

For me, growing up third-generation meant that I was very Americanized, to the point where I don’t speak my own language. I’ve had to really wrestle through what it means to be Chinese and Cantonese and Toysun.

If we can start looking at the world as this beautiful color spectrum, and not a monotone black-and-white palette, then maybe we can imagine that even the diversity of our language, culture, stories, and heritage all have something unique and valuable. We don’t need to assimilate or adapt to what is considered the larger narrative. Every narrative is unique and important, and we need all of them to create the world we want to live in.

Your book tells the story of three survivors of sexual violence--Nekesa, Mara, and Mubanga--as well as your journey to start Freely in Hope in Kenya and Zambia. What was it like for you, as an Asian American woman, to try and build relationships with these African women?

Ten years ago, there wasn’t as much intersection between Chinese and Kenyans, so Kenyans viewed me as white. If you weren’t Black, you were white, and since I’m American, I’m even more white.

Nikole Lim

But I’m a bit darker, so I wasn’t precisely white. I’m from the south of China, so they were like, “Why are you darker? You’re still white, but what are you?”

There was a lot of explaining I had to do: “I’m not white, but I am American. I am Chinese, but I’m not from China.” It took a long time for people from my community to understand what that meant and that my approach would therefore be different from most non-profit, white-centric, male-centric workers that infiltrated Kenya.

The thing that really united us was the fact that we shared meals together. Eating with our hands, staying in their homes, was, for most of the girls I served, something that most of the white Americans would refuse to do. For me, it was like, “If you’re given food, you’d better eat it.” I knew that from my own culture, so doing it in another context was easy.

I think what might have been more challenging was how we approached relationships. Storytelling in a communal, expressive space is very intuitive for Kenyans and Zambians. Sharing your story not only through narrative but through song, dance, rhythm, and food is something that was not translated for me in my culture.

They used song, dance, and narrative to tell their story in a way that wasn’t structured into a perfect, journalistic essay, and that was something that was so beautiful and so meaningful that I was grateful to learn from the survivors.

In your book, you talk about helping women who have experienced oppression to tell a more uplifting narrative of themselves that could bring liberation. How does one do that, exactly?

Storytelling is a process and journey beyond narrative. We believe that storytelling is the pursuit of your dreams. If you’re living into your dream, that’s the story you’re creating.

As survivors gain their own sense of autonomy through community and education, we equip them through leadership skills like program design, public speaking, or financial management, so that, through their leadership, they can go back to their communities and help others.

The storytelling platforms are programs designed and implemented by survivors. They come with their vision and their ideas about how they want to build a program that ends sexual violence. They pitch it to the team, we workshop it together, we find funding for it, and we implement it. That’s what helps create this new narrative where advocating against the violence that they experienced in their childhood allows their story to be redeemed and restored.

Can you map out passages in Scripture of God as storyteller and the ways he is with us and transforms our narratives?

Our foundational Scripture is Isaiah 61: ”The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor.” This is the first Scripture that Jesus uses to publicly proclaim himself the one who will provide liberation and freedom to the captives. The verse goes on to say that transformation will come. There will be beauty for ashes, joy for mourning, praise instead of despair, etc.

Isaiah 61 goes on to say that “They shall build up the ancient ruins; they shall raise up the former devastations; they shall repair the ruined cities, the devastations of many generations.” This is the part of Isaiah 61 that we don’t hear enough--that the oppressed will be the ones who rebuild, restore and renew. That’s why this transformation is so spectacular; the people you least expected will be the ones to usher in the liberation and realize their full transformation.

What words of advice can you give to your fellow Asian American brothers and sisters on how to pursue justice while also honoring their parents and family?

My particular challenge was to pursue my calling even at the risk of betrayal. That one’s hard one for Asians, because we don’t want to bring any sense of shame or dishonor to our family. But at the same time, if God is calling, that’s beyond what your family system understands. It might be perceived shame or dishonor, but in reality, God’s call is so much greater.

Early in my career, God was pushing me into doing something bigger with my life beyond being an international photographer. I was doing fairly well. My parents were pleased with that, saying, “Okay, we didn’t come all this way for nothing.”

When I was on the field and felt that these girls were calling me into something greater and God was challenging me to do something beyond photography, I called my mom and told her, “Mom, I’ve met all these girls and their dreams are so much larger than mine, and I want to help them. I’m thinking about starting an organization!”

My mom said, “Well, whatever you do, it better be financially viable. Period.” I didn’t talk to my mom for a few months after that. I had to choose: What am I willing to do at the risk of that perceived betrayal or perceived dishonor? I had to choose if I were to pursue this call that God was calling me to. I knew if I didn't, I would be miserable.

There were about two years of not very good communication and relationship with my parents. Later, I was invited to speak at a conference, and the poster for the conference featured me and Francis Chan and a bunch of other people. My father is a huge fan of Francis Chan, because he’s the only Asian pastor in mainstream-white-people land! The poster came out, and my dad was like, “Oh, what is this? I guess we should go.”

I shared my testimony about how my mom’s cancer was part of the transformation for me in recognizing God’s presence in the midst of suffering. It was the first time my parents had ever heard that story.

I didn’t know this at the time, but, after my mom’s treatment, she’d had a hysterectomy. This was hard, because she and my dad had wanted a third child, and now couldn’t have one. After my talk, my dad said that God spoke to him and said, “This is your third child, the person your daughter has become that is different from the child that was born.”

They could see the drastic change in me from an angry child that doesn’t want to speak up to someone who is publicly advocating against sexual violence. They understood that this calling that the survivors and God brought me into was something bigger than them, and that’s when they started supporting my work.

Photo by Jill Wellington from Pexels

Dr. Michelle Reyes is the vice president and co-founder of AACC.

Help us continue the work of empowering voices. Give today.