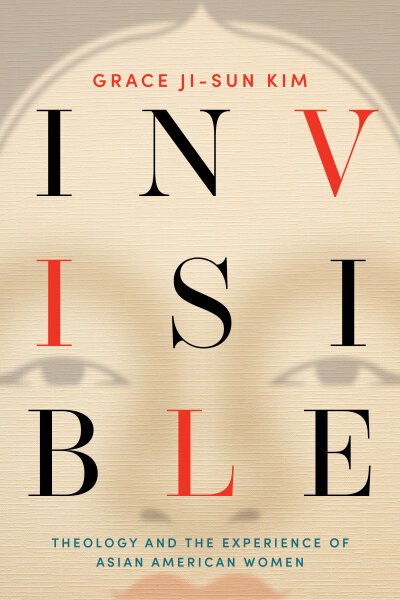

Invisible Book Review

By Isaiah Hobus

G

race Ji-Sun Kim’s voice is a needed voice, both for the AAPI community and the church at large. When I first opened Invisible, I was captivated. I struggled to put the book down amidst other responsibilities in my life. As an Asian American in our white dominant culture, I have struggled to find voices and representation that resemble and speak to who I am. Kim’s voice is one of the few voices that I find resonating deeply to the core of who I am in my Korean heritage while simultaneously challenging how I embody my faith, maleness, and culture in the world. I saw pieces of myself throughout this book, but more accurately, I saw the experience of my mom, sister, and other Asian women.

Kim, a Korean American theologian, immigrated with her family to Canada from a postwar Korea during a significant wave of Asian immigrants to North America during the 1960s and 1970s. However, in her family’s hopes for the American dream, they were met with heavy socioeconomic barriers, cultural dissidence, and racial discrimination. In Invisible, Kim recounts the fragmentation of her identity as an Asian woman by also being American. Her life is distorted by a double bind. On one hand, “[She] would be minimized to a mere idea of an ethnic tribe – rather than viewed as an individual, complex person – through the validating eyes of white people; it seemed it was them who had authority over who [she] was in society and what [she] represented in the world” (p. 9). On the other hand, “[she] discovered what people expect of Asian women through various stereotypes used to label and control…who are generally regarded as subservient, faceless, invisible objects” (p.12).

Invisible is largely a memoir, which may seem strange compared to other books written about theology. One might expect an outlined exegesis, an exploration of church history, or the strong usage of a particular theologian; instead, the reader will find a book doing theology that is grounded in the lives and experiences of Asian American women. For as Kim argues: “Theology is an experience of God in culture from one’s personal and contextual point of view” (p.126). Theology is not limited to be a language based in the white male experience of God; rather, theology is a global language.

In reality, personhood along with the context and experiences that make up a person is a rich source of theology. Oftentimes this tacitly goes unacknowledged inside the imagination of faith and the formulation of doctrine. As Kim notes: “the word ‘person’ itself comes from the Latin word persona which means, ‘an actor's mask.’ Thus, a person may be the clearest reflection of God among us who loves us and embraces the marginalized and invisible in our society.” (p.135). Culture, skin pigmentation, and facial features hold an inherent sacramental [reflective] nature of God’s love, presence, and embrace of persons. In short, Asian people are wound into the life of the Triune God. To degrade the nature of Asian women is to degrade the very nature of God. Where society passes over Asian women, the Triune God sees Asian women, for they are bound into the very life of God. Invisible flows from this conviction, making the voice of Asian women necessary. Kim offers new theological language to faith, uplifting the voices of marginalized Asian Americans and decentering the power of whiteness that is so often permitted to define our representations of God through theology.

A beautiful example of this is Kim recounting a cold winter walk to school with her sister. Following her family’s immigration, Kim came in touch with the Asian American experience. Her father struggled to hold a job, primarily due to his health; her mother often was subject to ridicule particularly for her struggle to speak English; and her family struggled with inadequate resources, so much so that it was considered splurging to take on the expense of buying beds. Kim’s despair eventually rose to the surface on this walk to school. On this extremely cold day, she was halfway to school in knee deep snow. She realized she had one shoe and a frozen wet sock. Telling her sister to wait, she went back to find her shoe. After backtracking Kim found the pocket of snow with the shoe. Kim recounts that something gripped her in that moment. She put her other shoe in the snow along with her dry foot. She sat, with her feet freezing. Kim, closing her eyes, wished no one would find her and time would escape. Kim eventually awoke. Her sister began to pull her up off the ground, putting her shoes on her feet, and jerked her back on her way to school, saying, “Do not tell mom and dad” (p.61,62).

This story haunted me. In one sense because of how often AAPI people not only repress their experience and marginalization, but also because how often the AAPI experience is passed over. I saw invisibility in its full effect: the ongoing struggle of learning to recognize and validate one’s own value (p.102). Kim, as an Asian American woman, had to reckon with what she lost in society's ongoing erasure of a group of people. Invisible courageously offers full witness to the invisibility of Asian women and to a God who sees. Kim ultimately asks her reader to reimagine faith in the God who makes all visible, whose spirit is in all people, and whose reign never ceases–defining our today.

Invisible reaches into the fullness of the Asian American experience amidst our diasporic identity. This book will resonate across the the diaspora speaking to Asian patriarchal culture, immigration, xenophobia, Chinese Exclusion Act, yellow peril, the hypersexualization of Asian women, the compartmentalization of AAPI identity to East Asian identity, and AAPI Hate crimes amidst COVID-19. This book is becoming increasingly relevant, particularly in light of the murder of Michelle Go and Christina Yunna Lee, and the one year anniversary of the Atlanta Massacre. This text is practical, beautiful, and grounded in a shared generational racial and gender trauma. I wish more books written on theology were as openly grounded in personhood. Regardless of your theological or faith background this book is a must read.

Photo by Erick Zajac on Unsplash

Isaiah Hobus is a recent graduate of Bethel University with a degree in biblical and theological studies, and currently a Master’s of Divinity student with an emphasis in Christian community development at Northern Seminary. He is also a youth outreach associate at a nonprofit ministry for teens, Treehouse Hope in Minnetonka, Minnesota, where he mentors teenagers. In his spare time, he enjoys reliving his days as a college athlete in cross country and track through runs, sticking his nose in a book, and guzzling black coffee.

Help us continue the work of empowering voices. Give today.